Krylov, Søndergård, LPO, Royal Festival Hall

Geoff DIggines, October 11, 2016

“Sergej Krylov is clearly one of the most distinguished violinists playing today.”

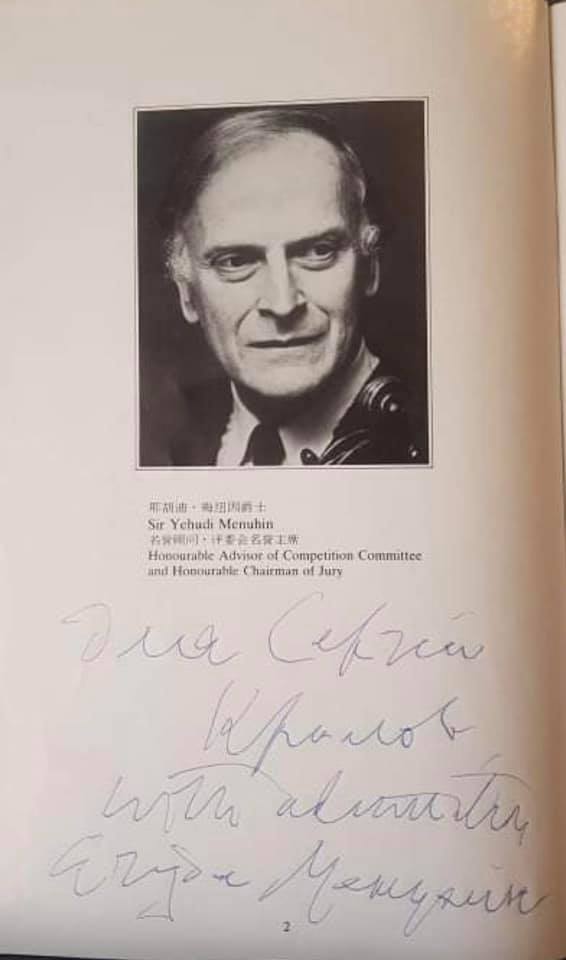

“I can’t imagine Menuhin or any other violinist dead or alive surpassing Krylov.”

Panufnik composed his Violin Concerto in 1971 for the veteran violinist Yehudi Menuhin who had requested the concerto. It was composed to be premiered by Menuhin with his Menuhin Festival Orchestra, and Menuhin performed the concerto in 1972 at the City of London Festival with the composer conducting. The opening ‘Rubato’ starts with a quasi-cadenza for soloist, which sets the mood of the movement. This is carried over by the orchestra (for strings only) which accompanies the soloist’s long cantilena. After a quasi-development section based on two intervals in minor and minor inn the flow of the music the solo cantilena re-emerges and brings the movement to an end with a shortened quasi-cadenza for soloist.

Tonight there was a wonderful dialogue between soloist and conductor. Both attended to the very flexible tempo indication ‘Rubato’. I had not heard Moscow trained Sergei Krylov before, but by tonight’s standards he is clearly one of the most distinguished violinists playing today. His tone is so diverse, as are his glissandi and pizzicato as heard in the concertos finale. He negotiates multi- stopping (chordal playing) with absolute assurance and integrity. Throughout the concerto Krylov deployed an absolute minimum of vibrato thereby playing with a tonal purity which so informs Panufnik’s design. I can’t imagine Menuhin or any other violinist dead or alive surpassing Krylov.

The Adagio, built on alternate minor and major triads initially in the orchestra, but then taken up by the soloist, as one commentator has noted, the dark minor thirds take the semblance of a Purcell- like descending bass line. The movement’s coda exudes a poetics of simplicity and reflexivity all ultimately expressed by the soloist in the tone of ‘molto tranquillo’ marked in the score.

The ‘vivace’ finale further explores the use of minor and major thirds – in the second section the melodic line initiates a minor triad as a kind of elaborated reflection from the first movement. In this movement the emphasis is very much on rhythm and constant cross-rhythms – except in the middle section- where the soloist plays a long cantabile sequence on a G-string, compellingly sustained by Krylov tonight. But all this is interrupted by short rhythmic constellations from the orchestra increasingly in dance mode. Panufnik wrote here that he wanted to convey the human feelings of joyousness, vitality and even some sense of humour.

As an encore Krylov played a brilliant and perceptive rendition of Ysayë’s ‘Obsession’ from his Second Violin Sonata in A minor, Op.27 with its intonations of the ‘Dies irae’.