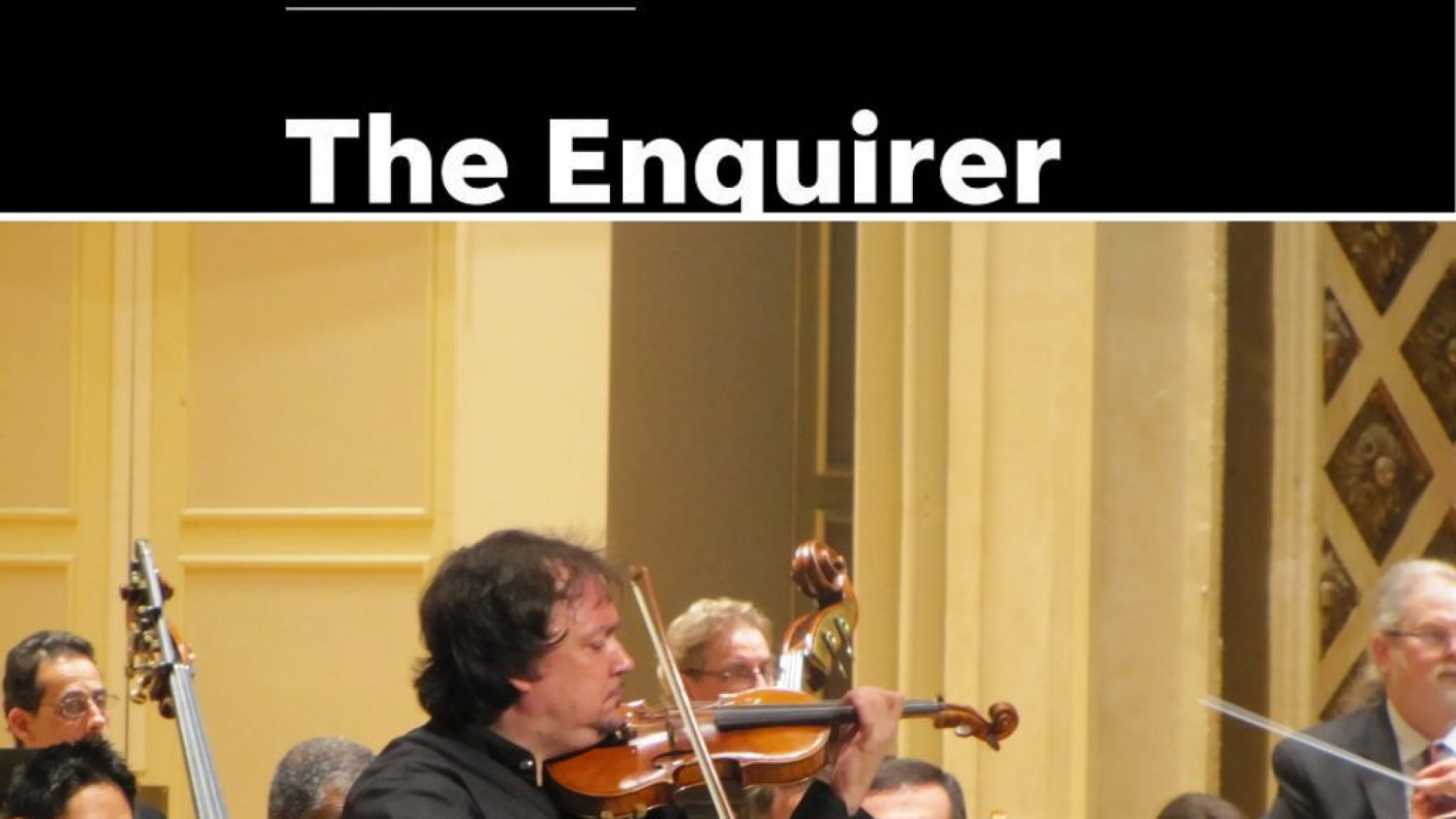

Krylov, Montanaro, CSO, Music Hall Cincinnati

Janelle Gelfand, 29 April, 2016

It was the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto like you’ve never heard before.

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra presented a new, 45-year-old Russian-Italian violinist named Sergej Krylov, whose electrifying technique in Tchaikovsky as well as in his encore, a Bach transcription, had listeners on their feet twice on Thursday in Music Hall.

The CSO had two newcomers in the hall for a light-hearted program of Italian-inspired music. Guest conductor Carlo Montanaro, who has a busy career directing opera around the world, led the orchestra in Mendelssohn’s “Italian” Symphony in the program’s second half, as well as two other audience favorites in the somewhat lengthy program.

You might wonder where Krylov has been hiding all these years. A winner of the Fritz Kreisler Competition among others, the Moscow-born artist has performed with the Atlanta Symphony, but his career is largely based in Europe. Born into a musical family, he played a stunning, big-toned violin made in 1994 by his father, the late Alexander Krylov. (The family emigrated to Cremona, Italy, so the maker is known as Alessandro Crillovi.)

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D Major is known for its technical displays, but Krylov added on an extra level of virtuosity with the whiz-bang way he flew through its challenges. He communicated with an unusually full, burnished sound, and crouched, turned and moved around as he played.

In his phrasing of Tchaikovsky’s glorious melodies, he liberally used the technique of pulling back and pushing ahead known as “rubato,” often sliding into notes in the romantic style of golden-age players.

The soloist’s interpretation was a bit too over-romanticized for my taste, but his technical wizardry took ones breath away. The first movement’s cadenza was attacked with bow flying, as if to say, “watch what I can do.” His runs were supercharged – sometimes at the expense of clarity and precision.

Krylov’s phrases in the slow movement were original, and he communicated with a haunting lyricism that drew the listener in. It was a riveting performance, as he traded phrases with wind players in this beautiful movement. The finale was as fast as I’ve ever heard it played. He dashed through its diabolical virtuosities, while at the same time seeming to challenge the orchestra to play faster and faster. The orchestra managed to keep up, and Montanaro never overpowered the soloist.

For an encore, the violinist put on another show in a transcription of the famous Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, originally for organ, attributed to J.S. Bach.

Montanaro’s conducting in the rest of the program was something of a mixed bag. Tchaikovsky’s orchestral gem, “Cappriccio Italien,” which opened the program, was inspired by a trip to Rome, and includes bugle calls and a tarantella. The conductor’s view was full of drama in the big moments, but lacked nuance, especially in the sunny folk music. Even though the opening fanfares were impeccably played by the CSO brass, tempos were very fast and the music didn’t breathe.

Mendelssohn, in the second half, made a different impression. Again, the maestro’s tempos were very quick, but that worked in Mendelssohn’s charming Overture to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The scampering fairy music was beautifully played by the strings, and the winds sparkled.

The conductor’s view of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4, which concluded the evening, was fresh and speeds were exhilarating. The lovely third movement, something of a throwback as a minuet, would have benefited from more warmth and charm. It was also too fast – the horn trio at its center was a strikingly slower tempo.

The finale, colored by traditional Italian dances, the saltarello and tarantella, was fleet and driving. The orchestra gave it a spirited performance, and special note goes to the flutes.